Mastering SOLID Principles with Go Examples

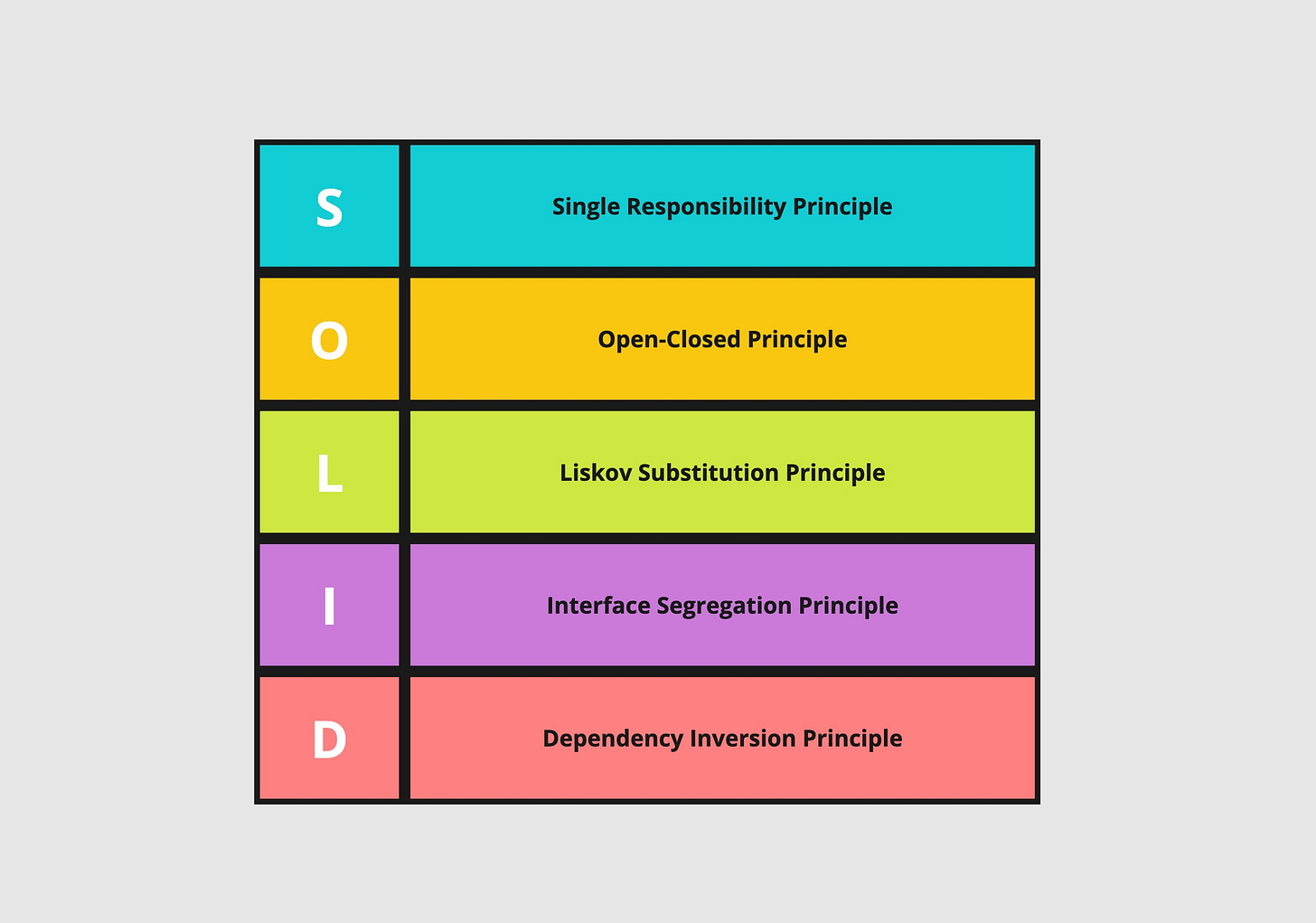

The SOLID principles are a set of design guidelines that help developers write more maintainable, scalable, and testable code.

Building software is an ever-shifting challenge. To navigate this complexity, developers rely on proven design principles to craft code that's robust, adaptable, and easy to manage. One such set of principles is SOLID (first introduced by Robert C. Martin).

SOLID stands for: Single Responsibility, Open-Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion. Each principle plays a vital role in fostering maintainability, scalability, and testability in your programs.

Although Golang is not a purely object-oriented language, we can still apply SOLID principles to improve our Go code. Throughout this post, we'll delve into each principle, explore its meaning, and discover how to leverage it effectively within Go.

S - Single Responsibility Principle

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) dictates that a struct/package should focus on a single well-defined area of functionality. Imagine each struct as a specialist with a specific expertise. This keeps your code organized and reduces complexity. Changes to the struct's functionality are isolated, making maintenance and future updates a breeze.

“A class should have one, and only one, reason to change.”

Robert C. Martin

Go excels with structs, not classes. But fear not, the SRP still applies here. Imagine each struct as a tightly-knit module responsible for a single, well-defined task. This modular approach keeps your code clean, reduces complexity, and promotes maintainability.

The magic of SRP extends to Go packages as well. Ideally, a package should focus on a single area of functionality. This minimizes dependencies and keeps things organized. By embracing SRP in both structs and packages, you create a foundation for clean, maintainable, and scalable Go applications.

Some examples of good packages:

encoding/json - provides encoding/decoding of JSON.

net/url - parses URLs.

Not so good examples:

utils - dumping ground for miscellany?

Let’s see an example in Go where we have a struct Survey with some properties and few methods, GetTitle(), Validate() and Save():

You can find the source code in our Github repository.

package survey

type Survey struct {

Title string

Questions []string

}

func (s *Survey) GetTitle() string {

return s.Title

}

func (s *Survey) Validate() bool {

return len(s.Questions) > 0

}

func (s *Survey) Save() error {

// saves the survey to the database

return nil

}Our current Survey struct seems to be designed well, except for the Save() method. Its presence introduces a violation of the SRP. With both data storage and survey logic residing in the same struct, maintenance, testing, and extension become more challenging.

To adhere to the SRP, we should separate these concerns:

package survey

type Survey struct {

Title string

Questions []string

}

func (s *Survey) GetTitle() string {

return s.Title

}

func (s *Survey) Validate() bool {

return len(s.Questions) > 0

}

type Repository interface {

Save(survey *Survey) error

}

// One of many possible implementations

type InMemoryRepository struct {

surveys []*Survey

}

func (r *InMemoryRepository) Save(survey *Survey) error {

r.surveys = append(r.surveys, survey)

return nil

}

func SaveSurvey(survey *Survey, repo Repository) error {

return repo.Save(survey)

}Now, the Survey struct is only responsible for managing survey data, while the Repository interface and InMemoryRepository struct handle database operations.

O - Open-Closed Principle

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) is a cornerstone of good software design. It dictates that software entities (classes, modules, functions, and the like) should be designed with future growth in mind. This means they should be open for extension, allowing for the addition of new features and functionalities, while remaining closed for modification. Modifying existing code to accommodate new needs is risky, as it can introduce bugs and make future maintenance a nightmare.

“A module should be open for extension but closed for modification.”

Robert C. Martin

Back to our Survey example. Let’s add a new method to our struct - Export(), which could export the survey data into some external service/storage. Since there could be multiple export destinations, the Export() method has a switch block.

package survey

// ...

func ExportSurvey(s *Survey, dst string) error {

switch dst {

case "s3":

// export to s3

return nil

case "gcs":

// export to gcs

return nil

default:

return nil

}

}If we need to add support for another service, the current implementation would require modification, which violates OCP.

To adhere to the OCP, we can define an Exporter interface so we can add new exporters for different destinations without modifying the existing codebase.

package survey

// ...

type Exporter interface {

Export(survey *Survey) error

}

type S3Exporter struct{}

func (e *S3Exporter) Export(survey *Survey) error {

return nil

}

type GCSExporter struct{}

func (e *GCSExporter) Export(survey *Survey) error {

return nil

}

func ExportSurvey(s *Survey, exporter Exporter) error {

return exporter.Export(s)

}This adheres to the OCP, promoting code flexibility and maintainability. Our code is open for extension (we can add new exporters) but closed for modification (we don’t need to change the Export() function).

L - Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) ensures objects can be swapped without breaking the program. While Go lacks traditional inheritance, interfaces achieve this. Any type can "implement" an interface simply by having methods that match its signature. This promotes flexibility – code using the interface can work with various types as long as they fulfill the contract.

“If S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S, without breaking the program”

B. Liskov

In Go a good example of LSP could be the io.Writer interface:

type Writer interface {

Write(buf []byte) (n int, err error)

}The magic of io.Writer lies in its ability to write a byte slice into any stream: files, HTTP response, etc.

Now back to our Survey struct, we can add a method Write() which writes the survey object somewhere. We can simply let it accept io.Writer so the implementation can decide where to write it to.

func WriteSurvey(s *Survey, writer io.Writer) (int, error) {

b, err := json.Marshal(s)

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

return writer.Write(b)

}The user of this function now have a lot of flexibility, as they only need to use some struct that implements io.Writer, for example:

file, err := os.Open("file.go")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

survey := &Survey{Title: "Feedback Form"}

WriteSurvey(&Survey, file)I - Interface Segregation Principle

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) states that clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use. This principle encourages creating smaller, more focused interfaces rather than large, monolithic ones.

“Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use.”

Robert C. Martin

Again, Go's io package is a great example. It has multiple small interfaces and their combinations, check for example io.Reader, io.ReadWriter, io.ReadCloser, io.ReadWriteCloser, etc.

In our Survey example, let’s imagine we have multiple question types: text and dropdown. We could define a common Question interface.

type Question interface {

SetTitle()

AddOption()

}

type TextQuestion struct {

title string

}

func (q *TextQuestion) SetTitle(title string) {

q.title = title

}

func (q *TextQuestion) AddOption(option string) {

// not supported as text fields don't have options

}

type DropdownQuestion struct {

title string

Options []string

}

func (q *DropdownQuestion) SetTitle(title string) {

q.title = title

}

func (q *DropdownQuestion) AddOption(option string) {

q.Options = append(q.Options, option)

}The AddOption() method in the Question interface sticks out. It doesn't make sense for a TextQuestion and violates the ISP. Here's how we can follow ISP and improve the design: split the Question interface into smaller, more focused ones:

type Question interface {

SetTitle()

}

type QuestionWithOptions interface {

Question

AddOption()

}

type TextQuestion struct {

title string

}

func (q *TextQuestion) SetTitle(title string) {

q.title = title

}

type DropdownQuestion struct {

title string

Options []string

}

func (q *DropdownQuestion) SetTitle(title string) {

q.title = title

}

func (q *DropdownQuestion) AddOption(option string) {

q.Options = append(q.Options, option)

}D - Dependency Inversion Principle

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) states that high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

In simpler terms, DIP advises that your code should depend on interfaces or abstract classes rather than concrete classes or functions. This inversion of control reduces the coupling between different parts of the software, making it more modular, extensible, and easy to test.

“Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.”

Robert C. Martin

As an example we can introduce a SurveyManager struct that handles survey creation, as you can imagine it relies on a database.

type InMemoryRepository struct {

surveys []*Survey

}

type SurveyManager struct {

store InMemoryRepository

}

func NewSurveyManager() *SurveyManager {

return &SurveyManager{

store: InMemoryRepository{},

}

}

func (m *SurveyManager) Save(survey *Survey) error {

return m.store.Save(survey)

}The bad design here is that it heavily relies on InMemoryRepository, violating the principle that high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules.

Again, interfaces and constructors can help us here to decouple things:

type Repository interface {

Save(survey *Survey) error

}

type SurveyManager struct {

store Repository

}

func NewSurveyManager(store Repository) *SurveyManager {

return &SurveyManager{

store: store,

}

}

func (m *SurveyManager) Save(survey *Survey) error {

return m.store.Save(survey)

}Conclusion

The SOLID principles serve as a cornerstone for crafting clean, maintainable, and scalable software. While the specific implementation details may vary depending on the programming language (like using interface composition in Go instead of inheritance), the core tenets of SOLID remain universally applicable. By embracing these principles, developers can write code that is more adaptable, easier to test, and ultimately more resilient to change, regardless of the language they choose.

Again, you can find the source code in our Github repository.

If the code syntax highlighting was there it will be more better to read code

Don do `SetTitle`.

title is already exported, so no need to have a setter method on it.

Instead make `title` unexported, then you can provide a setter.